In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, a spectrum of opportunities lie ahead for restaurant operators and investors all over the world. Aaron Allen, from Chicago-based Aaron Allen & Associates, shares his insights regarding the future of the region’s F&B industry. Aaron Allen is the CEO and chief strategist of Aaron Allen & Associates, a global strategy firm focused exclusively on the foodservice and hospitality industries, with a strong specialization in the Middle East.

In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, a spectrum of opportunities lie ahead for restaurant operators and investors all over the world. Aaron Allen, from Chicago-based Aaron Allen & Associates, shares his insights regarding the future of the region’s F&B industry. Aaron Allen is the CEO and chief strategist of Aaron Allen & Associates, a global strategy firm focused exclusively on the foodservice and hospitality industries, with a strong specialization in the Middle East.

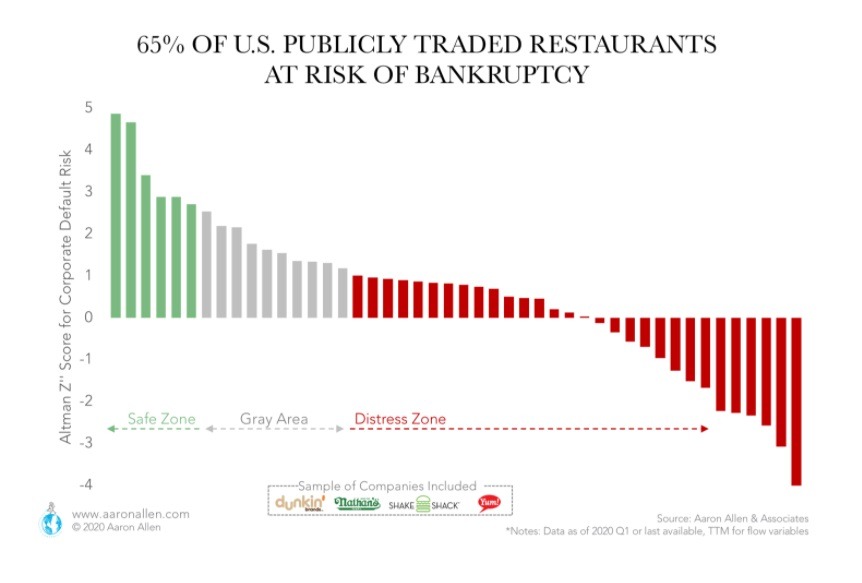

Whereas close to two-thirds of publicly traded restaurant chains in the U.S. are at risk of bankruptcy, in the Middle East, foodservice companies traded on stock exchanges seem to be less exposed by comparison, but short-term liquidity is the biggest risk factor.

Whereas close to two-thirds of publicly traded restaurant chains in the U.S. are at risk of bankruptcy, in the Middle East, foodservice companies traded on stock exchanges seem to be less exposed by comparison, but short-term liquidity is the biggest risk factor.

Savvy investors can look at this time of uncertainty as an opportunity to broaden the landscape of potential attractive acquisitions. While some may be moving into this scenario opportunistically — smelling blood in the water — the most successful are realizing that this can be the perfect timing for a mutually advantageous acquisition to optimize portfolios and gain market share.

The risks

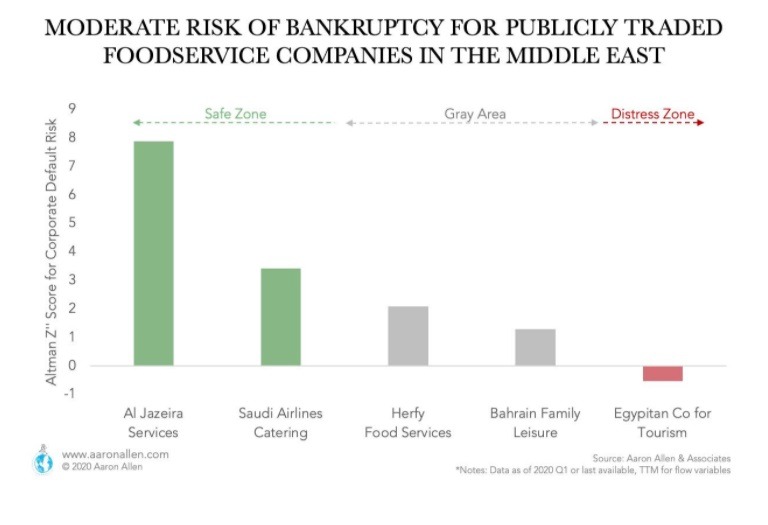

The following includes insights relative to the Altman-Z” Score for publicly traded foodservice companies in the Middle East. This score is used to help assess potential risk for bankruptcy based on a company’s financial standing. The Altman-Z” Score, a variation of the Altman-Z Score — which is commonly used to calculate the credit strength of manufacturing companies — is based on key financial metrics, including: current assets, current liabilities, total liabilities, EBIT, total assets, retained earnings and the book value of equity. Generally speaking, an Altman-Z” Score greater than 2.6 is deemed “safe,” a number between 1.1–2.6 is in the “gray area,” and anything under 1.1 is in the “distress zone.”

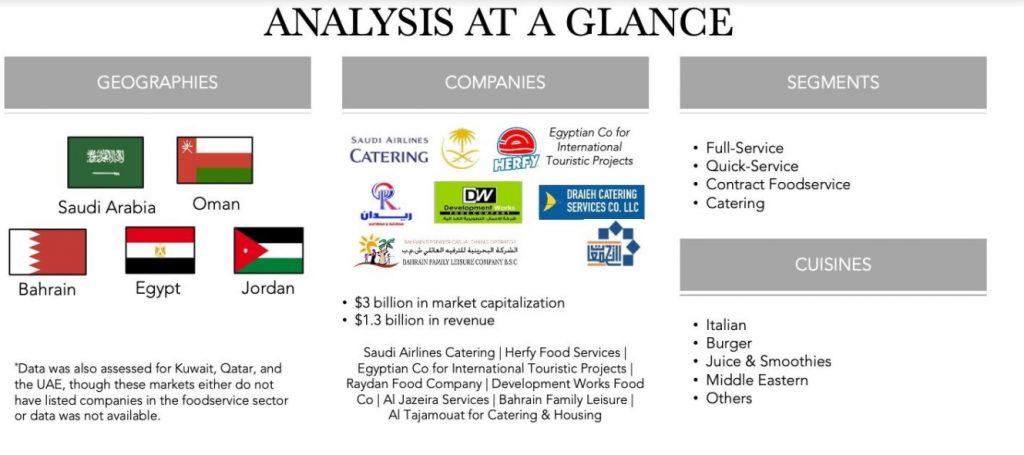

These calculations were completed in June 2020 using Q1 2020 data for Middle East publicly traded restaurant companies or the last available data (depending on companies’ fiscal year in the analysis set). A total of eight companies are included in the analysis ranging in service styles (QSR, fast-casual, casual dining, etc.), but only five have complete data to calculate the Z’’-score.

These are not predictions nor forecasts but rather calculations based on financial standing. Many restaurant companies operating with different models (highly franchised systems versus wholly corporate owned systems, for instance) have naturally varied financial metrics which impact the calculations and financial performance.

Key findings of the analysis include:

- The balance sheets for publicly traded foodservice companies in the Middle East seem to be stronger than those based in the U.S.; out of five companies, only one is in the distress zone.

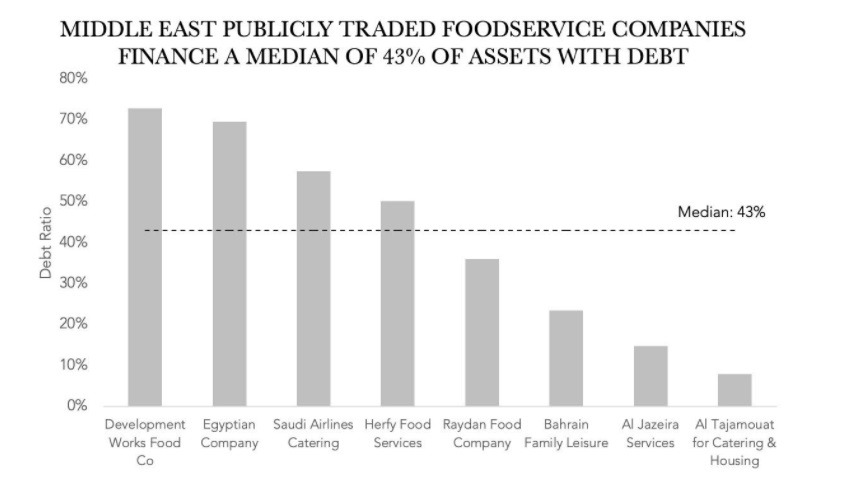

- Overall debt levels are not the biggest indicator of performance; as a median, Middle East public foodservice companies finance 43 percent of their assets with debt (roughly half the level of debt U.S. restaurants have).

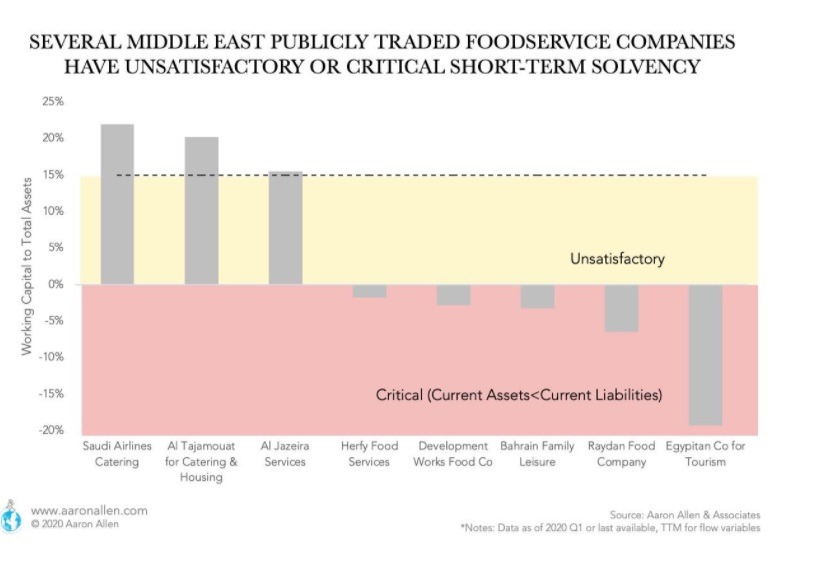

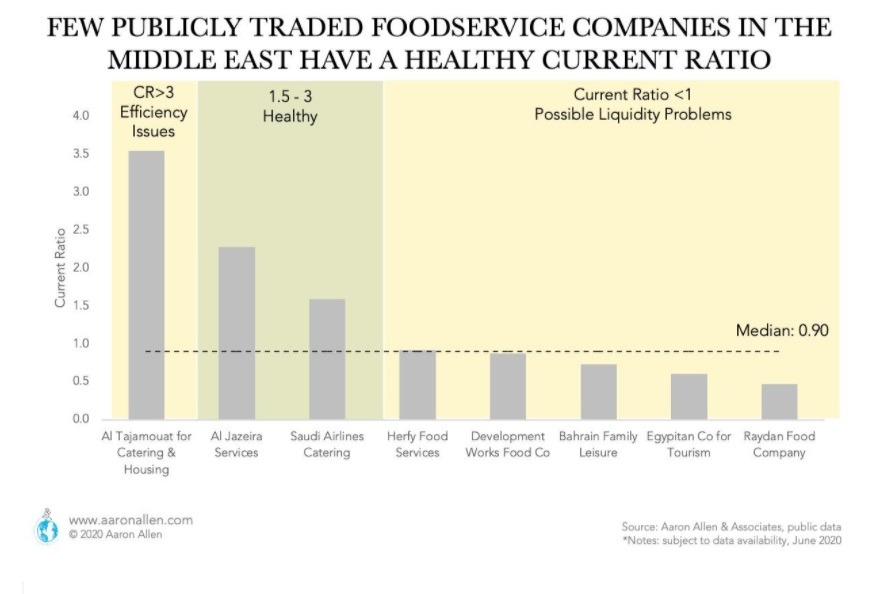

- Short-term liquidity is a larger part of the issue, as 63 percent of the companies studied have an unsatisfactory or critical current ratio and are thus exposed to liquidity risks.

- In the Middle East’s foodservice industry (considering eight public companies), the current ratio reached a median of 0.90 (Q1 2020), meaning that the current assets are not enough to cover current debt.

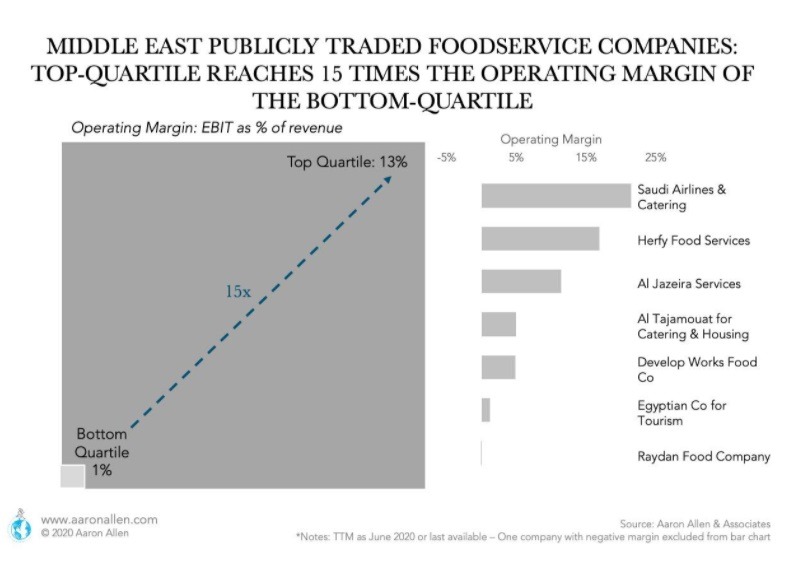

- The top quartile of foodservice companies are outperforming the bottom-quartile by 15 times in terms of operating margin.

Troubling effects

The effects of the pandemic on the restaurant industry in the Middle East are understandably troubling. GDP growth projections for 2020 are negative for both the KSA and UAE — which will have a large impact on the broader GCC market. This will reshape the global restaurant industry in a way that’s sized appropriately for the size of the pandemic.

A total of eight companies are included in the analysis — ranging in service styles (QSR, fast-casual, casual dining, etc.) — but only five have complete data to calculate the Z’’-score. Notwithstanding data availability, the insights into restaurants debt and liquidity also reveal the weaknesses (and strengths) of several major players. These companies represent USD 1.3 billion in revenue and about USD 3 billion in market capitalization.

While Saudi Arabia has seen close to 400 bankruptcy requests in the past few months (across sectors) and Dubai DIFC has made plans to protect employees of companies that go out of business, the story among publicly traded companies in the Middle East seems different.

From the sample of five companies with full data available to factor the Altman-Z” score, we found that only one was classified as in the “distress” zone based on the calculation.

Public foodservice companies have reasonable overall debt levels

Public foodservice companies have reasonable overall debt levels

As a median, publicly traded foodservice companies in the Middle East finance 43 percent of their assets with debt. This is roughly half the level of debt restaurants in the U.S. have. Some of the most exposed businesses that would take a lot of debt and equity to restore them will take a haircut on valuation. For many investors, it will be the right moment to grow their portfolios with some strategic add-ons.

Short-term liquidity can cause problems

Short-term liquidity can cause problems

The working capital to total assets ratio reveals the percentage of remaining liquid assets once total current liabilities are paid out compared to the company’s total assets. As a rule of thumb, ratios lower than 15 percent are generally considered unsatisfactory, and negative values are considered critical.

Though the number of publicly traded foodservice companies in the Middle East is limited, 63 percent are in these zones. For many restaurant chains, investors will have to step in to solve the liquidity crisis ahead of other critical initiatives focused on innovation and re-inventing the economic model.

The higher the current ratio (current assets to current liabilities), the more a company can pay its short-term debt. Of the public companies analyzed, the current ratio reached a median of 0.90 (Q1 2020). For many restaurant chains with current assets that are not enough to cover current debt, existing debt levels are also not sustainable. This scenario will likely lead to plenty of distressed restaurant assets in the near future, which will spur activity as the global pause on M&A lifts as travel restrictions are loosened.

The higher the current ratio (current assets to current liabilities), the more a company can pay its short-term debt. Of the public companies analyzed, the current ratio reached a median of 0.90 (Q1 2020). For many restaurant chains with current assets that are not enough to cover current debt, existing debt levels are also not sustainable. This scenario will likely lead to plenty of distressed restaurant assets in the near future, which will spur activity as the global pause on M&A lifts as travel restrictions are loosened.

Large differences in performance explained by investment

Large differences in performance explained by investment

There are many proof points to demonstrate the differences in approach of top-quartile and bottom-quartile performers. When we look at operating margins, the differences are staggering. Among publicly traded foodservice companies in the Middle East, the operating margin of the top quartile is 15 times the margin for the bottom quartile.

The top performers are also allocating more resources toward R&D and building proprietary systems that are reinforcing the moat around their business and locking out their competition. This is a great time to make operations faster, leaner and more agile to optimize margins and achieve top-quartile performance.

U.S. restaurant bankruptcy risk by comparison

U.S. restaurant bankruptcy risk by comparison

When analyzing public restaurant companies headquartered in the U.S. by the same metric, we found that more than six in every ten restaurant chains are in the “distress zone” — either being highly leveraged, having low earnings or a combination of both. Even with an injection of liquidity, it will not be enough to cover what the losses are, with the industry down tens of billions per month right now it’s going to be very hard to get back, even once restaurants are at full capacity.

It’s not all doom and gloom

It’s not all doom and gloom

Restaurant bankruptcies have always been a topic of conversation in the industry. Very seldom can there be discussions about foodservice operators without the topic of the failure rate of restaurants coming up. That said, foodservice is actually a very resilient business. There is no question — regardless of geography — we will all continue to eat; the how and where will change so dramatically that hundreds of billions of dollars in global consumer foodservice spending will shift from incumbent brands to innovators and more convenient and profitable models.

Those that are most optimistic often tend to be either those that are under-informed and bubbly optimists by nature — or, they are those that have done their homework and developed a silver-lining investment thesis. Foodservice is a multitrillion-dollar global industry that has remained as consistent as inflation and population growth for decades and spend has been irreversibly redirected in a single quarter — displacing and shifting hundreds of billions of dollars in global consumer discretionary spending.

While it will be fatal for some and fortune-building for others. This period will usher in a fresh wave of consolidation through mergers and acquisitions. In many cases, recessionary M&A involves distressed and dislocated assets that can be purchased for pennies on the dollar. However, it’s not always predatory or unwelcome. In our view, this period of change will just be accelerating the transformation that was already underway and being profitably harnessed by industry leaders.